The Brain-Mouth Connection: The Surprising Link Between Oral and Mental Health

Mental health plays a huge role in a person’s general well-being and physical health, and it has been proven time and time again that our minds and bodies are deeply connected. One major factor of this includes oral health, which has been said to be a window to overall health but is often overlooked in the medical community. For this reason, several GoMo Health Concierge Care programs integrate oral health, especially within cancer care, as patients can experience challenging oral side effects to their treatment.

People struggling with mental health issues may be at a higher risk for developing oral health problems. Certain medications can also cause or exacerbate oral health issues ultimately bringing additional stress to the patient. Healthcare professionals including medical and dental health providers can collaborate to bring awareness to these issues and address them. Our partners at NYU Oral Health Nursing and Education Practice dive deep into the brain-mouth connection in the latest blog post below.

By Jessamin Cipollina, MA

Mental health plays a significant role in oral health. People struggling with mental health issues such as anxiety and depression may be at higher risk of developing oral health problems like tooth erosion, cavities and gum disease. There are gaps in oral healthcare needs for individuals who struggle with mental health, including overall lack of awareness of the “brain-mouth connection” and the importance of promoting oral health among patients with mental health issues. Findings from evidence-based studies reveal that those with mental health problems are more likely to be affected by poor oral health and underutilize oral health services.1-5 Those struggling with mental illness are often affected by the social determinants of health that limit access to regular dental care. Side effects of medications that are used to treat mental health problems, including antipsychotics, antidepressants and mood stabilizers, are associated with a higher risk for xerostomia, tooth decay, oral infections, periodontal disease, oral pain and tooth loss.1,3-5 Dental and medical health care providers can collaborate on best practices for managing and preventing the many oral health problems that are associated with mental health issues.

In the US, 45 million people are living with some form of mental illness that negatively impacts their day-to-day life, including their oral health.6 Isolation and financial hardships that many experienced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic deeply affected mental health status across the globe.5-7 Closure of dental offices in the first year of the pandemic exacerbated oral health issues and prolonged treatment. Even with dental offices reopening and safety precautions in place, many who experience dental anxiety or anhedonia and lack of motivation related to depression are not likely to schedule a dental cleaning. Many who lost their jobs during the pandemic remain uninsured and unable to afford dental care out of pocket. Additionally, people who struggle with their mental health may feel insecure about their poor oral health due to lack of home oral hygiene and, as a result, are reluctant to see their dentist.1,3,5,7 Dental care may not be easily accessible for those with mental health issues, but health care professionals in psychiatric, pharmaceutical and primary care settings have an opportunity to promote the importance of oral health care with their patients.

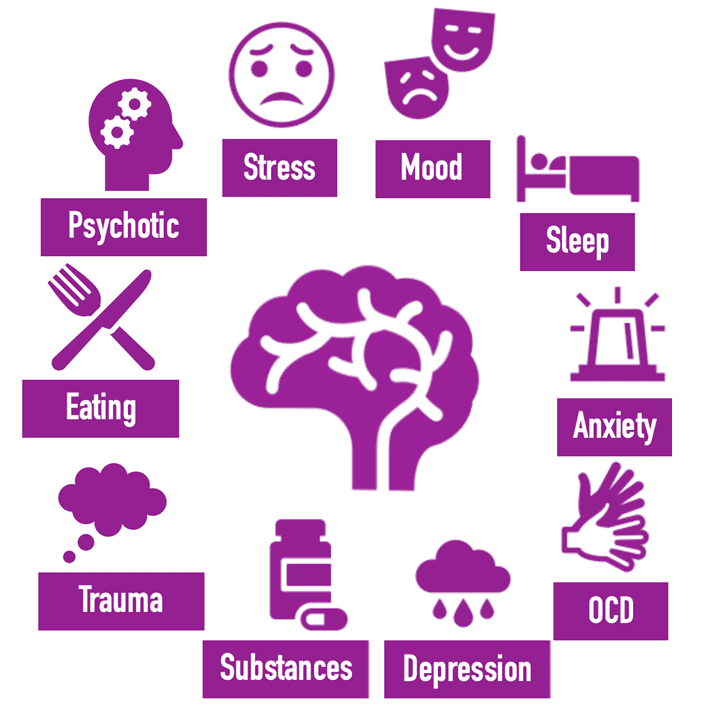

Mental illness is multifaceted and complicated to manage, and the many forms of mental health issues out there include numerous symptoms and treatments that can lead to increased risk for oral health problems. People with psychiatric disorders are at risk for oral health problems due to side effects of medications and neglect of their oral hygiene. For all mental health conditions, early detection, prevention and treatment of oral health problems is essential to improving patients’ overall health and quality of life.2,5,7

Stress. Any level of stress can have physical effects on the body. Stress affects the immune system, sleep, eating, and personal hygiene. People who are experiencing stress may also grind or clench their teeth (bruxism) periodically during the day and when sleeping, which can cause mouth pain, gum recession and tooth fractures. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly increased incidence of cracked teeth due to stress related to personal, social and financial hardships.2,5

Mood Disorders. Mood disorders, such as bipolar disorder, often cause over-brushing that may damage gums and cause dental abrasions and mucosal or gingival lacerations. Bipolar patients treated with lithium and/or anti-psychotics experience higher rates of xerostomia and stomatitis. Those who are treated with mood stabilizers are at increased risk for gingival hyperplasia and periodontal disease.5

Sleep. Lack of sleep can impair immune system functioning which can lead to increased risk of harmful inflammation and infection throughout the body, particularly in the vulnerable oral cavity. Difficulty sleeping is associated with increased risk for periodontitis and tooth decay. Lack of sleep can lead to poor nutritional choices, such as increased intake of coffee and snacking on food high in sugar and carbs throughout the day. Lack of sleep can also be due to stress or bruxism.5,8

Anxiety. Many people experience dental anxiety and dental phobias and, as a result, will neglect home oral health care and/or avoid going to the dentist. Additionally, medications that treat generalized anxiety disorders can cause dry mouth (xerostomia) which can lead to tooth decay. People who struggle with anxiety often experience bruxism and temporomandibular joint disorders (TMJ) that cause oral pain.1,5

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders (OCD). For people with OCD, brushing and flossing can be turned into repetitive, compulsive habits. Over-brushing and flossing can cause enamel erosion and tooth sensitivity.5

Depression. People who struggle with depression often neglect various aspects of their self-care. They do not feel motivated to carry out day-to-day hygiene practices and this lack of motivation can contribute to poor food and nutrition choices and poor oral hygiene. Depression is also associated with higher abuse of alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco, which may cause tooth erosion and decay.3-5

Substance Use/Abuse. Use of substances is a common coping mechanism among those struggling with mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, mood disorders and others. In addition to being a standalone issue, substance abuse is rampant among those struggling with mental illness. Abused substances include those that are prescribed (e.g. opioids), illicit (e.g. cocaine, methamphetamine) and legal (e.g. alcohol), and all of these contribute to oral health problems such as xerostomia, tooth decay, tooth loss, bruxism, periodontitis and mucosal lacerations.5

Trauma. Traumatic experiences can stay with a person for their entire life. Those with significant physical and mental trauma histories may experience dental anxiety and phobias, trauma triggers, when faced with situations that include health professionals working at close proximity to their mouth and using dental instruments in the mouth. People who have experienced trauma are more likely to avoid dental care. Careful consideration and small steps need to be taken in preparing patients for what will happen during their dental visit.1,3,5

Eating Disorders. Disordered eating behaviors such as vomiting and restricting food can cause oral health problems. Acids from vomiting make patients with eating disorders more susceptible to tooth decay and enamel erosion. Those who under-eat or restrict food may not receive enough iron and/or calcium, as well as have a weakened immune system, which can predispose them to tooth decay and oral infections.5

Psychotic Disorders. Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders increase risk for serious health problems, like metabolic syndrome, that increases risk for periodontal disease. Individuals who suffer from a psychotic disorder often demonstrate poor motivation related to personal care and hygiene, and often avoid dental and other necessary health care due to delusions, paranoia and/or trauma.5

Dental and medical professionals have a unique opportunity to collaborate by educating patients and their caregivers, students and other health care providers about the importance of good oral care in improving health outcomes for those with mental health problems. An interprofessional approach for improving mental health and oral health can include dentists, primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, psychiatrists, physician assistants, pharmacists, nutritionists, community health workers and social workers, among others. All health professionals can encourage their patients who struggle with mental illness to adopt good home oral care practices like brushing and flossing teeth regularly, along with other home health habits like reducing sugar intake, exercising, smoking cessation, and reducing or eliminating substance use.

When making referrals or recommending care, it is important to think about the barriers that many people experience in accessing both mental health and dental care services. Those without health insurance may not be able to afford regular health care services and check-ups. Dental disease is concentrated among populations with low socioeconomic status, and many people must make difficult financial choices when seeking dental care. It is the role of health professionals to assess, diagnose, manage oral health problems within their scope of practice and refer their patients appropriately. Many patients with mental illness may have a dental benefit through Medicaid and public insurance. However, insurance coverage does not guarantee access to needed services. We call on health professionals everywhere to collaborate and engage with one another across oral health and mental health care settings to effectively improve the mental, oral and overall health and well-being of this population!

Interested in learning more about oral health management and solutions?

Schedule a Consult Today!References:

- All 4 Oral Health. The Mind-Body Connection: How Mental Health Can Impact Oral Health. March 6, 2015: OHNEP. Accessed May 30, 2022. https://all4oralhealth.wordpress.com/2015/03/06/the-mind-body-connection-how-mental-health-can-impact-oral-health/

- CareQuest Institute for Oral Health. The Connection Between Oral Health and Mental Health. 2022: Research Brief. Accessed May 30, 2022. https://www.carequest.org/resource-library/connection-between-oral-health-and-mental-health

- Tiwari T, Kelly A, Randall CL, Tranby E, Franstve-Hawley J. Association between mental health and oral health status and care utilization. Front Oral Health. 2022;2:732882. doi:10.3389/froh.2021.732882.

- Pitułaj A, Kiejna A, Dominiak M. Negative synergy of mental disorders and oral diseases versus general health. Dental and Medical Problems. 2019;56(2):197-201. doi:10.17219/dmp/105253.

- National Council for Mental Wellbeing. Oral Health, Mental Health and Substance Use Treatment: A Framework for Increased Coordination and Integration. 2022. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/NC_CoE_OralhealthMentalHealthSubstanceUseChallenges_Toolkit.pdf?daf=375ateTbd56.

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide. March 2, 2022: Press Release. Accessed May 30, 2022. https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

- Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1049-1057. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

- Alhassani AA, Al-Zahrani MS. Is inadequate sleep a potential risk factor for periodontitis? PLoS One.2020;15(6):e0234487. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234487.

Find Us Online